If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

By Paul Saltzman, Chicago Sun-Times

By Paul Saltzman, Chicago Sun-Times

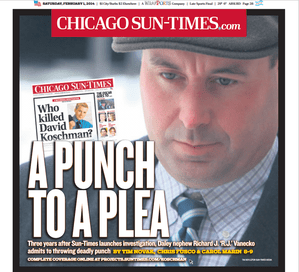

On Jan. 31, 2014, a nephew of former Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter in a death a decade earlier.

Richard J. “R.J.” Vanecko admitted doing exactly what an investigation by the Chicago Sun-Times had revealed in early 2011 he did — and what police and prosecutors had twice refused to charge him with doing:

Punching a much smaller man named David Koschman in a drunken encounter outside the late night bars on Division Street in Chicago’s Rush Street nightlife district. Knocking him to the ground with a single punch. And causing such devastating trauma that Koschman died of massive brain injuries 11 days later without ever regaining consciousness.

After first uncovering the whodunnit, reporters Tim Novak, Chris Fusco and Carol Marin kept pursuing the story of what happened that night — and in the two botched criminal investigations that followed.

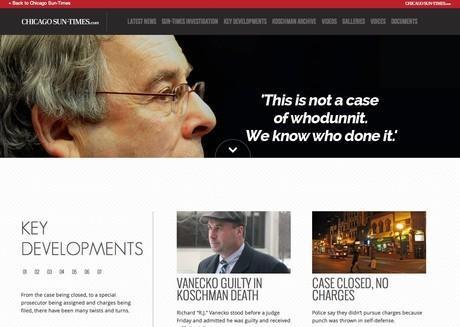

Their work ended up leading to the court-ordered appointment of a special prosecutor, the Daley nephew’s guilty plea and jailing, and a continuing investigation by the FBI into possible police corruption.

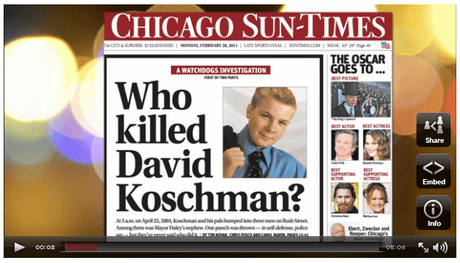

This story was pure enterprise. Novak decided it was time to finally get to the bottom of what happened to David Koschman — and to do it before Daley, who after a record-long tenure at City Hall wasn’t seeking reelection, left office.

Before he could even think about trying to get at the obvious question — whether being the mayor’s nephew had kept Vanecko from being charged — Novak, joined by Fusco and Marin, needed to figure out what happened that night, which the police had never explained.

And they weren’t about to now, refusing at first to release even a police incident report with basic information. They couldn’t, they said, because the investigation technically remained open — despite the police superintendent saying in 2004 no one would be charged.

None of the stories done in 2004 had identified anyone other than Vanecko and Koschman.

And Koschman’s mother didn’t want to talk. She felt burned by a TV reporter she’d opened up to years earlier who ended up not doing a story.

So the reporters started with Koschman’s online death notice. It included a “guest book” in which people could offer condolences. The reporters tracked down everyone who did. Most didn’t know — or wouldn’t talk about — what happened or who might have been with Koschman. But one woman talked about Koschman and passed along the names of four friends who’d been out with him.

The reporters tracked them all down. They said everyone was drunk, their friend David had accidentally bumped into a someone in another group of drunken revelers who took offense, and the two men had exchanged words. It wasn’t physical. But neither would let it go. Out of nowhere, another guy in the other group punched Koschman. Then, the man Koschman had argued with and the one who punched him ran off.

The mother heard from people the reporters spoke with and, convinced of their sincerity, agreed to talk.

The reporters identified the friends who were out with Vanecko — friends from prominent families.

They tracked down the now-retired detective who’d led the 2004 investigation as well as the retired superintendent who’d dismissed the matter as an unfortunate incident involving “mutual combatants.” Nonetheless, the police decided to take a new look at the 7-year-old case as a result of the reporters’ questions.

On Feb. 28, 2011, and March 1, 2011, the Sun-Times published the first two stories of 175 Novak, Fusco and Marin have written on the case to date. They produced a narrative that laid out most of the key elements of what happened that night in 2004. They also uncovered a number of unusual — though admittedly unexplained — elements in the way the case was handled by police and prosecutors.

Then, they heard from a witness they’d spoke with — one of two “unbiased witnesses” prosecutors had cited as saying Koschman “was the aggressor and had initiated the physical confrontation.” He told the reporters that was “a flat-out lie.”

Not put off by the case being closed, the reporters documented discrepancies in the official story — which, along with the witness’s “flat-out lie” statement, prompted calls for further investigation and resulted in the city inspector general deciding to investigate.Soon after, the police announced they had closed their new investigation without seeking charges, though they did identify Vanecko for the first time.

Their stories carried great emotional power. That was the result of meticulously detailed reporting. It was one thing, for instance, for the dead man’s mother to say it was terribly hard to watch her son die. It was something more to be able to detail exactly what was done to prolong his life during the 11 days he lay in a coma — details they got by having the mother sign off on getting her son’s hospital records for them.

Stories like that — and others regarding the calls (not entirely genuine) for an outside investigation — kept the story alive.

After Daley left office, the reporters found the new administration of Mayor Rahm Emanuel more amenable to releasing some of the police files denied to them under Daley — records they had continued to press for, turning to the state attorney general to challenge the initial denials of the records’ release.

One of those reports — a formerly “missing” file that, more than seven years later, had suddenly reappeared — turned out to be key. It noted a witness’ statement that Vanecko had been “very aggressive.” And on the back of one page, someone (apparently with a spelling problem) had scribbled “Dailey sister son” — an indication that the police, despite their denials, had known early on about the killer’s family link to the mayor.

By the end of 2011, Koschman’s mother had two lawyers — experienced in police corruption cases and working pro bono — file a motion asking a judge to appoint a special prosecutor to re-investigate her son’s death, citing the Sun-Times’ reporting.

The judge agreed, declaring “the system has failed” David Koschman and appointing a former U.S. attorney to investigate not only Koschman’s death but also the conduct of the Chicago Police Department and the Cook County state’s attorney’s office.

Even as the special prosecutor’s investigation stretched into more than 17 months, and even after Vanecko was indicted, the reporters kept pressing to learn more about the police handling of the case, most notably obtaining from sources a report showing the “‘Lost’ Koschman files weren’t lost after all” but had been removed from the police department without authorization.

After the special prosecutor ended his investigation without charging anyone other than Daley’s nephew, the reporters have continued to pursue the story. Among their exclusives: an interview with a grand juror troubled that the panel couldn’t charge any of the police.

Beyond the reporting, what made this story turn out as it has was support from above at the Sun-Times — from our owners and top management. Through some turbulent times for the paper, they stood by us. They didn't bow to the outside pressure they certainly felt. They made the commitment to allow us to stay with this story. Without that support, this doesn't happen.

A big challenge, having produced such a high volume of stories (as well as columns, video reports, editorials and editorial cartoons), was finding the best way to organize, highlight and archive all of this work online. So we bought and tweaked software (built on a WordPress platform) that made it possible to present the entire body of work via a separate website linked transparently to the Sun-Times’ main site.

This website — http://projects.suntimes.com/koschman — also includes additional written and video material, created specifically for this portal, looking atkey players and at the reporting process. There’s also a searchable database of key documentation, linked through documentcloud.org.

This undoubtedly will grow, as the reporters continue, more than three years after breaking the story, to dig into what’s developed into one of the most ground-shaking newspaper investigations Chicago has seen.

Chicago Sun-Times projects editor Paul Saltzman edited the paper's Koschman coverage.

Follow reporters Tim Novak, Chris Fusco and Carol Marin on Twitter

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.