If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

Lamont Pride was a wanted man the day he fatally shot a New York City police officer during a 2011 robbery. Officials had already passed up opportunities to lock up Pride, who was wanted in connection with a North Carolina shooting. And when the fugitive appeared in a Brooklyn court on a drug charge, a judge aware of the warrant also decided to let him go. A few weeks later Officer Peter Figoski was dead.

USA TODAY reporter Brad Heath followed coverage of the high-profile case.

“This must be out of the ordinary,” Heath remembered thinking. “I wonder how often this happens.”

This month he published the answer. Across the country, he found, more than 180,000 fugitives get away just by crossing state lines. In some places it’s as easy as driving over a bridge or going home to the suburbs. Some of the wanted, like Pride, go on to commit more crimes. Victims often are left in the dark.

In 2012 Heath started calling jails and sheriff’s departments asking about their ability to track inmates and fugitives. None of the agencies he talked to kept the data he sought. They also wouldn’t release their fugitive databases.

The data, he learned, was tied to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center, a secret database used by federal, state and local agencies to collect criminal justice information.

Heath filed two requests with the FBI for the confidential data set. The information he received was heavily redacted, revealing only the agency that inputted the warrant, the name of the offense charge, and the extradition limitations. Case numbers and last-known addresses were omitted, despite Heath’s request.

“What we had was a very anonymous data set,” he said.

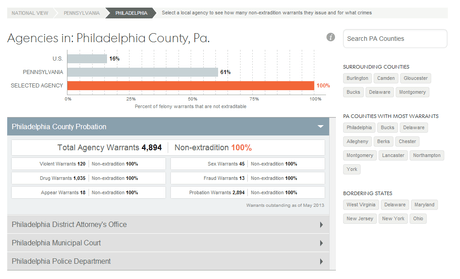

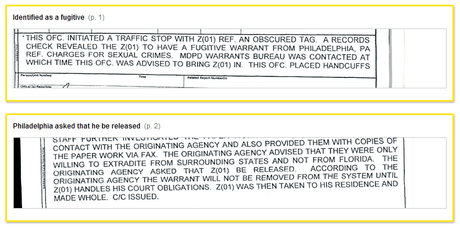

Heath turned to state and local police and court records to fill in the details the FBI withheld. The limited NCIC database allowed him to identify cities, like Philadelphia, that had high numbers of warrants flagged as non-extraditable.

Pennsylvania State Police provided warrant records – still anonymous – and case numbers. Heath used the police incident numbers to look up files in the state court system. Only then did he start to find suspects’ names.

Gannett affiliates helped in the reporting process, using local police records and interviews to identify individual cases.

Gannett affiliates helped in the reporting process, using local police records and interviews to identify individual cases.

“It was a great, really remarkable thing,” Heath said of the Gannett partnership. The idea wasn’t new, “but we were trying to take advantage of so many talented reporters who can not only localize, but contribute to the national story, too.”

Fugitives all over the country were hiding in plain sight. It wasn’t hard for Heath to track down some of them. Their current addresses were listed in sex offender registries or court paperwork. Other times they were sitting in another city’s jail.

“We asked a lot of people to talk, and I was surprised at how many actually did,” Heath said.

The relative ease of getting the wanted to sit down for photos and interviews – some recorded on video – further highlighted the glaring hole in the justice system: Officials knew exactly where to find fugitives; they simply didn't want to go get them.

To talk to a fugitive in Maryland, Heath left a note on a business card at the man’s home. A few hours later Heath had an email from him.

“I think there’s a lot of trust involved,” he said. “They have to have some confidence that we’re not looking to jam them up. The speech I gave was, ‘I’m not here to help or get you in any more trouble, just to give you a chance to explain.’”

Reaching out to crime victims posed a greater challenge. Decisions about extradition were usually made in secret, Heath learned, leaving many victims to believe the accused had been arrested and convicted. Heath often had to deliver the bad news, a task he knew would likely open old wounds.

“That was difficult,” he said. “Telling them, ‘here’s everything I know.’ A lot of them didn’t know. It’s the part I really didn’t look forward to, but it was necessary.”

While many law enforcement agencies were reluctant to talk about their extradition decisions, officials in Philadelphia – a focus of Heath’s stories – were not.

When Heath presented his findings, the second in command of the Philadelphia district attorney's office agreed that his analysis was accurate. Officials walked through each extradition case and explained their choices.

“I thought that office was just about as forthcoming as any bunch of public officials I’ve ever talked with,” he said.

Other officials, including those responsible for approving extraditions, were in disbelief when Heath and the Gannett affiliates showed them the numbers. Police in some of the country's highest-crime cities – Philadelphia, Atlanta and Little Rock – reported to the FBI that they wouldn't pursue at least 90 percent of their felony suspects if they went to other states.

“Everybody tends to look at this as, I’m inputting a warrant today,” he said. “I did not come across any agency that had looked at their extradition process this way.”

Put simply, USA TODAY did what law enforcement agencies across the country had failed to do – they looked at the big picture.

As a result, many agencies say they’re reversing or reevaluating their extradition practices. A top prosecutor in Macon, Ga. said he’ll ask to end non-extradition practices for people wanted on felony warrants. And in Philadelphia, prosecutors are reviewing thousands of felony cases and approving extradition for “several hundred.”

Follow USA TODAY reporter Brad Heath and IRE web editor Sarah Hutchins on Twitter.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.