If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

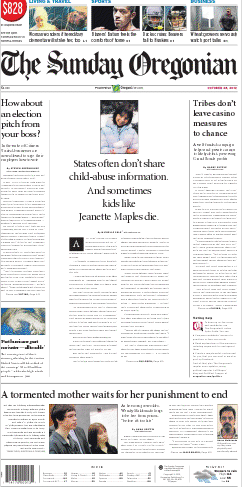

There were signs of problems before 15-year-old Jeanette Maples died of starvation and abuse in Oregon in December 2009. Although child services had been involved in the case, residents were shocked to find that Maples death had not been prevented. Oregonian reporter Michelle Cole wanted to know what, if anything, could have been done to change the circumstances. Through her investigation of the case, she uncovered problems with child welfare services that extend outside of Oregon and into national child welfare regulations. The deficient child abuse monitoring system continues to affect cases across the United States.

There were signs of problems before 15-year-old Jeanette Maples died of starvation and abuse in Oregon in December 2009. Although child services had been involved in the case, residents were shocked to find that Maples death had not been prevented. Oregonian reporter Michelle Cole wanted to know what, if anything, could have been done to change the circumstances. Through her investigation of the case, she uncovered problems with child welfare services that extend outside of Oregon and into national child welfare regulations. The deficient child abuse monitoring system continues to affect cases across the United States.

In Maples case, child welfare reports showed a history of abuse and neglect, but reports had only been filed in California, where the abuse occurred. When Maples’ family later moved to Oregon, the documentation of Jeanette’s abuse remained in California, even after suspected abuse led an Oregon case-worker to file requests. The requests were repeatedly denied.

Cole discovered this during a search of the state’s records on the Maples case. “Oregon has a law requiring the Department of Human Services to release records concerninga child fatality in cases where there has been abuse,” she said. Cole asked for the minutes of what Oregon calls it’s "critical incident response team,” which meets “whenever a child known to child welfare officials is killed,” Cole said.

Behind The Story is a weekly series from IRE exploring the investigative process. If you have a suggestion for the series, email web@ire.org.

From these and court documents, Cole was able to uncover the larger story behind the Jeanette Maples case. “The Oregon Department of Human Services' ‘critical incident review’ following Jeanette's murder mentioned the lack of information, rather obliquely,” Cole says. It raised questions for her. “I started this story by going to the top child welfare managers and asking them if they thought this was a systemic problem or an isolated case. They assured me that there is an information-sharing issue in their field.” From there, Cole spoke with managers and agency workers, all of whom confirmed the problem and were happy to document the extent. “They even did a two-week tally for me of the number of inquiries to and from other states,” Cole says.

Had it not been for the child welfare managers and the case-workers, many of whom shared personal stories, Cole may not have continued her investigation. The national child welfare advocates she initially interviewed, “were fairly lukewarm about the subject. And, frankly, not that helpful,” Cole said. Cole would have stopped there, but caseworkers revived the story, telling Cole that a lack of time and resources prevented many from pursuing the matter further.

Cole discovered that Congress had mandated that states share information with one another in 2006, passing a law requiring the establishment of a national database of proven child abuse cases. There was no deadline for the project or plan for its implementation. Since then, states have continued their own slow progress. Cole hopes her reporting encourages the federal government to get more involved. “I think states want to do what's right for families and children,”she says, “they simply need a little help and guidance.” Many officials have reached out as a result of Cole’s reporting, including the detective in the Maples case, Aaron Hoberg, and Oregon State Representative Carolyn Tomei.

Michelle Cole, formerly a reporter at The Oregonian, is a writer and researcher Gallatin Group, a public affairs firm in Portland. She can be reached at michellecolewilliams@gmail.com.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.