If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

A story that helped change the way Chicagoans digest crime stats started with suspicion.

Immersed in a different crime-related piece, Chicago Magazine Features Editor David Bernstein and Contributing Writer Noah Isackson noticed something amiss with the statistics. When their trusted police sources voiced skepticism, the early trappings of an idea took hold.

In the spring of 2013, fresh off a year of 507 murders in Chicago, the most of any U.S. city, Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy started celebrating what the stats showed was a drastic turnaround in the amount of crime on Chicago streets. Crime rates, the two proclaimed at press conferences, were lower than they had been in more than 40 years. But Bernstein and Isackson weren’t convinced.

Plugging the numbers into a spreadsheet spurred a 12-month investigation, which culminated in a two-part series titled, “The Truth About Chicago’s Crime Rates.” Heavily anchored by data and lifted by strong sourcing and documentation, the report found several instances where police had misclassified crimes. Several clear homicides were reclassified as “death investigations,” which don’t count toward the city’s murder totals, or closed as noncriminal incidents.

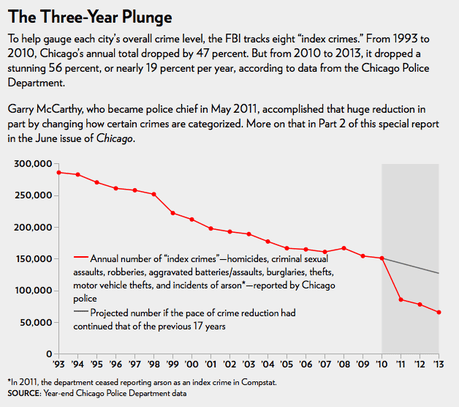

Bernstein and Isackson’s first step was to build a spreadsheet with the number of “index crimes” – the eight violent and property crimes police report to the FBI – for each of the last 20 years. The resulting graph gave visual evidence that the period saw a steady drop of 3-to-4 percent a year – until 2011.

“All of a sudden, when you get to 2011, it goes off a cliff,” Bernstein said.

Bernstein and Isackson discovered 10 homicides misclassified by police, but they investigated countless others.

A base of current and former police sources, some of them high-ranking, provided guidance throughout the process.

“Sources would tell us, ‘This one doesn’t look quite right; that one doesn’t look quite right,” Isackson said. “And once we’d been getting that information for several months, you could start to pick up different cues and signs.”

The two tracked cases through news clips and kept an eye on the ones that seemed suspicious. They maintained close contact with their sources.

FOIA helped them dig deeper into investigations. They uncovered the ways the narrative of a death changed or the ways that information from the medical examiner contradicted the police investigation. They sought documents from the Chicago Police Department and from the Cook County clerk and medical examiner’s office.

But along the way, while placing FOIA requests, they remained mindful of their sources’ confidentiality. They requested documents in generalities, seeking annual lists of investigations rather than honing in on specific cases, so as to not hint at a specific tip.

Still, several leads produced no fruit.

“Some (cases) were handled appropriately,” Bernstein said. “Some we couldn’t get enough reporting on. The thing you have to keep in mind is that we were just two reporters with a limited amount of time and a limited amount of resources.”

The two figured the story went deeper, but they also knew that an article about crime rates would get the most attention at the brink of Chicago’s homicide-heavy summer months. So, they began to write.

The two set aside the cases that didn’t involve a death and started writing the homicide sections. Their story grew quickly, morphing into more than 14,000 words over two parts, the first focused on homicides and the second looking at other crimes. The articles ran online in April and May, respectively, and hit newsstands in the May and June issues.

One of the most challenging but rewarding parts of the process for Bernstein and Isackson was developing sources. Earning the trust of cops took time. Their editor, Elizabeth Fenner, provided it.

“We needed a long runway to do this,” Bernstein said. “Our editor Beth had our back all the way.”

Armed with the support of Fenner, Bernstein and Isackson hit the pavement. The sensitivity of the topic, they found, contributed to skepticism from the police, who were already distrustful of the press.

Bernstein and Isackson broke bread with cops, holding long conversations during which they often felt they were being tested. The more they proved they knew, the more their sources felt comfortable talking.

“Police officers would ask us when we’d meet, ‘Is your magazine really willing to go there? Are you really willing to challenge the numbers in this way?’” Isackson said.

They were, and their Rolodex proved vital.

Also important in the building of sources, no doubt, was a decision by Bernstein and Isackson – and backed by their editor – to keep anonymous the law enforcement officials quoted in their stories. The cops had much to lose by talking publicly, and Bernstein and Isackson opted to protect their anonymity, a move they said allowed them to cultivate the right sources.

“There was no other way to get this information,” Isackson said. “But at the same time, we cross-checked and cross-checked and cross-checked the information.”

It was clear immediately that Bernstein and Isackson’s reporting had struck a nerve.

When part one hit the web in April, it was quickly passed around on social media. Other news media covered the report. And maybe the greatest indicator of impact: by April 8, one day after the story ran online, a 12-page memo from Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy hit Fenner’s inbox. He denounced the magazine for the piece. Fenner publicly backed her journalists.

Despite the public buzz, Isackson said he’s heard from families of murder victims identified in the story who say that police have done little to nothing to remedy the misclassifications, which downplayed their family members’ deaths.

Bernstein and Isackson say they are encouraged, though, by the way dialogue about crime rates in the city has shifted. Colleagues working for the city’s dailies have added nuance to their reporting, they say, and the general public has gained some healthy skepticism.

“It’s permeated into the conversation now,” Bernstein said. “People are finally starting to say, well, can we trust the police department with these numbers?”

Shawn Shinneman is a graduate student at the Missouri School of Journalism and a student employee at IRE. Prior to graduate school, he spent two and a half years reporting daily news at a newspaper in the Chicago suburbs. You can follow him on Twitter here or email him at shawns@ire.org. Follow Chicago Magazine on Twitter @ChicagoMag.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.