If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

On Thursday, The Charlotte Observer and the News & Observer in Raleigh won bronze in the Barlett & Steele Awards for Investigative Business Journalism, funded by the Donald W. Reynolds National Center for Business Journalism, for their series "Prognosis: Profits," in which the reporters dissected the finances of large healthcare institutions and discovered inflated prices, lawsuits against thousands of needy patients and minimal charity care to the poor and uninsured -- all practiced contradicting the core missions of the hospitals.

On Thursday, The Charlotte Observer and the News & Observer in Raleigh won bronze in the Barlett & Steele Awards for Investigative Business Journalism, funded by the Donald W. Reynolds National Center for Business Journalism, for their series "Prognosis: Profits," in which the reporters dissected the finances of large healthcare institutions and discovered inflated prices, lawsuits against thousands of needy patients and minimal charity care to the poor and uninsured -- all practiced contradicting the core missions of the hospitals.Ames Alexander and Karen Garloch of the Charlotte Observer and Joseph Neff of the News & Observer reported on the story, and Ames and Neff shared some details of their reporting on a recent story in the series showing inflated prices on cancer drugs.

Where did the idea for the reporting come from?

We did a five-part series in April, "Prognosis: Profits," that exposed how large nonprofit hospitals gained greater market power through acquisitions, purchases and alliances. This market power has allowed them to negotiate ever higher payments from insurance companies, resulting in higher profits and robust cash reserves. The big hospitals made healthy profits even during the worst years of the recession.

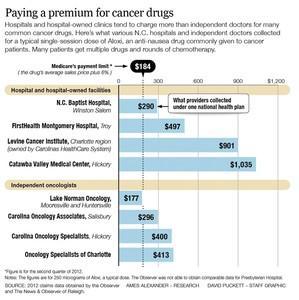

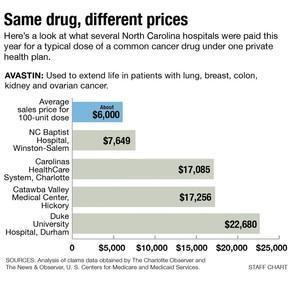

This story was a follow-up to the series. We heard from sources that hospitals were inflating prices on cancer drugs, sometimes charging two, five, ten or even 50 times the average sales price. Almost all cancer drugs are administered in an outpatient setting, where hospitals are paid a percentage of their charges. Hence, the higher the charge, the more money the hospitals make.

We also found that hospitals are dominating the market on cancer care. Hospitals are acquiring formerly independent oncology clinics and employing oncologists – and that immediately raises prices because the hospital charges are higher.

We also reported how many hospitals took advantage of a federal program known as 340B to purchase their drugs at steep discounts - anywhere from 20 to 50 percent. The 340B program was designed so that hospitals could provide drugs to poor or uninsured patients, but there's little evidence that hospitals are passing on the savings to patients. Rather, the hospitals use the program to purchase drugs for all outpatients, including those with private insurance.

What was the most interesting part of the reporting process?

Learning how the hospital billing system works and how drugs are priced. There is a lot of helpful data from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on the average sales prices of drugs and what Medicare will allow. It was fascinating to see the large gulf between what hospitals likely paid for many drugs and what they received. But such markups are hidden from patients.

What are some setbacks you faced? How did you work around them?

Some hospitals refused to answer basic questions – such as how much they spent on cancer drugs and how much revenue those drugs generated. The state’s large hospital chain, Carolinas HealthCare System, initially provided only a brief statement in response to our questions and did not make officials available for an interview. But we kept asking, and eventually got an interview with the system’s president, which allowed us to more thoroughly tell the system’s side of the story.

Some patients, meanwhile, had heart-rending stories but didn't want to have their names used in print, usually because they were afraid it would damage their relationships with their doctors. But we kept interviewing more patients until we had enough who were willing to share their bills and tell their stories publicly.

What were the most interesting things you found that didn’t make it in to the story?

At the Duke Cancer Center, the charge for a unit of Avastin was $324. At the Duke eye clinic, owned by the same nonprofit entity, the charge was just $65. Duke never provided an explanation about why the charges differed so much.

Which documents and data were crucial to this story, and how did you get them?

We obtained and analyzed a private database of more than 5,000 chemotherapy claims. That allowed us to confirm what some experts suspected: that hospitals and hospital-owned clinics were typically charging more for cancer drugs than independent doctors – often much more. This database is not publicly available, but we got it by cultivating sources.

We also made great use of publicly available Medicare data showing the average sales price of specific cancer drugs. By comparing those numbers with the charges and reimbursement figures from our database, we were able to calculate how much hospitals were marking up the price of each drug.

By talking with lots of patients, we also obtained dozens of individual bills and explanation of benefits (EOBs) from insurance companies. Those gave us a better picture of how much cancer patients are typically billed for a single round of chemotherapy. It’s not uncommon for those charges to exceed $30,000, we found.

But the bills and invoices only go so far. At our request, some patients obtained itemized bills, which show the charge for every aspirin, bedpan and unit of drug administered.

We also wanted to determine what percentage of the oncology world was controlled by hospitals. We obtained the directory of licensed physicians from the N.C. Medical Board, isolated the subset of medical oncologists and determined whether they were hospital-affiliated or independent. The numbers were startling: 88 percent of oncologists in the Raleigh-Durham area, for example, worked for hospitals.

What tools did you use to organize the data?

We used Microsoft Access to analyze the data on chemotherapy claims. We also used Excel to organize and analyze data on N.C. oncologists. That helped us document how most oncologists in the Charlotte and Raleigh regions are now employed by hospitals.

The Charlotte Observer used Document Cloud to annotate one large chemotherapy bill for its readers.

//

After this experience, what advice can you offer fellow investigative reporters?

What do you hope will change as a result of your reporting?

More transparency. Many patients have no clue about what they're being charged, what the drugs and services they receive cost hospitals, and how prices compare among providers. It’s not good for an informed citizenry.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.