Transparency Watch

MuckRock analysis finds 27 percent of FOIA requests still unfulfilled after three months

MuckRock, a public records service that files and tracks requests on behalf of journalists, researchers, activists and historians, recently analyzed 907 requests completed by its users. The analysis found about 42 percent of federal Freedom of Information Act requests were completed on time, and 27 percent of those 907 requests are still without a response after…

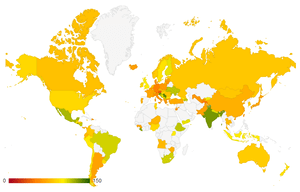

Read MoreCountries with longtime FOI laws have less corruption, better human development

The Center for Law and Democracy rates FOI law effectiveness by country. Freedom of Information Act advocates have consistently claimed that institutionalizing the right to information will benefit countries, particularly in addressing corruption. They are not lying. By comparing indices on corruption, human development, and years of having an FOI law across 168 countries, I…

Read MoreCalifornia transit agency changes records policy in midst of investigation

inewsource out of San Diego reports that in the midst of an investigation into a local transportation agency, the North County Tranist District, the agency voted to adopt a policy change that would direct its employees to delete certain emails after 60 days, a drop from the previous email retention policy of two years. Despite…

Read MoreOpen government advocates say additions to California budget bill would devastate public records law

The California legislature has added wording to the state budget bill that open government advocates say would devastate the state’s public records laws. The added language would allow government officials to turn down records requests without written record of the basis for denial. Officials would no longer need to cite legal reasons for withholding information.…

Read MoreDepartment of Justice expedites IRE request, assigns officer

The Department of Justice has expedited IRE’s request for records pertaining to the surveillance of news organizations and has assigned an officer to handle the request. Last week, IRE reported that it had filed the request and that the DOJ had sent a letter of acknowledgement but had not assigned the request a reference number…

Read MoreFinalists announced for Golden Padlock award

Investigative Reporters and Editors has released the list of finalists for its inaugural Golden Padlock Award honoring a U.S. government agency for its unrelenting commitment to undermining the public’s right to know. JobsOhio: Ohio Gov. John Kasich and the state legislature are nominated for creating a non-profit economic development entity exempt from public records disclosure laws, despite…

Read MoreIRE seeks Department of Justice records on surveillance of news organizations

The revelation last month that the Department of Justice seized phone records from the Associated Press turned out to be just the begining of major disclosures about government surveillance, which according to recent reports includes mass collection of phone and internet server data by the National Security Agency. But the Department of Justice surveillance targeting…

Read MoreMaking sense of the government surveillance news

News of the National Security Agency’s surveillance of phone records and internet server data is breaking fast. Yesterday The Washington Post and The Guardian released records that show the U.S. Government has been collecting a vast cache of data spanning audio and video chats, emails, and stored files under a surveillance program known as PRISM.…

Read MoreLawmakers take aim at home for Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

The Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism, which operates the WisconsinWatch.org website, faces a threat from the state legislature that could kick the nonprofit organization out of its home at the University of Wisconsin. The center, a pioneering effort in regional nonprofit investigative reporting, is run by longtime IRE member Andy Hall, and has conducted more…

Read MoreFOIA request to CDC took five years to fulfill

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers itself to be one of the nation’s foremost scientific institutions, dedicated to transparency and evidence-driven policies. It is fair, therefore, to ask this question: What happens when the CDC brazenly ignores the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), taking more than five years to fulfill a journalist’s information…

Read More The IRE office will be closed from December 25th to January 5th.

The IRE office will be closed from December 25th to January 5th.